The First Hungarian Republic

On November 16, 1918, Prime Minister Károlyi Mihályi and other representatives of the Hungarian National Council [Magyar Nemzeti Tanács] that had emerged as Hungary’s legislative power at the end of the First World War proclaimed the establishment of the Hungarian People’s Republic [Magyar Népköztársaság] to succeed the Kingdom of Hungary as the name and form of the Hungarian state. The term People’s Republic had not yet come to designate communist forms of government, thus the new state can be regarded as the First Hungarian Republic.

The First Hungarian Republic lasted for just four and a half months, until a leftist alliance of the Party of Communists in Hungary and the Hungarian Social Democratic Party declared the establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic [Magyarországi Tanácsköztársaság] after coming to power on March 21, 1919.

The First Hungarian Republic is strongly identified with Count Mihály Károlyi, who served as the short-lived republic’s sole head of state.

———————————————————————————————————————-

Formation of the Hungarian National Council

The Hungarian National Council formed in Budapest on October 23, 1918 in order to fill the political void emerging with imminent defeat of Austria-Hungary in the First World War and the resulting collapse of the Hungarian noble oligarchy that had ruled the Kingdom of Hungary since the establishment of the Dual Monarchy in 1867 (see the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy).

The council was composed of the following anti-war, anti-oligarchy, pro-independence opposition parties: the Independence and ’48 Party [Függetlenségi és 48-as Párt] under the leadership of Count Mihály Károlyi; the Bourgeois Radical Party [Polgári Radikális Párt] under the leadership of editor and social scientist Oszkár Jászi; and the Hungarian Social Democratic Party [Magyarországi Szociáldemokrata Párt] under the leadership of Zsigmond Kunfi.

On October 25, the Hungarian National Council issued a 12-point liberal-socialist political program that included the following main stipulations:

-resignation of the government and dissolution of the National Assembly;

-immediate end of the war, recall of Hungarian troops from all fronts, and termination of the military alliance with Germany;

-Hungary’s complete independence and territorial integrity;

-establishment of “a fraternal alliance of equal peoples” in economic and political alliance with Austrian, German, Polish, Czech, South Slav and Ukrainian nation states if possible;

-and introduction of universal and secret suffrage, property and social-political reform as well as the freedoms of association and assembly.

The Aster Revolution

Citizens and demobilized soldiers in Budapest began placing the Aster [őszirozsa] flowers that were in bloom at the time in their hats and caps to symbolize support for the Hungarian National Council and Count Károlyi. On October 28, 1918, a large group of these supporters gathered in Pest and marched toward Buda Castle, where they intended to present Archduke Joseph August of Austria, the official representative of Habsburg King Charles IV, with a demand that he appoint Count Károlyi to serve as prime minister. Mounted gendarmes attempted to disperse the demonstrators as they approached the Chain Bridge, while others opened fire on those who continued to advance, killing three people and wounding more than 50.

The so-called Chain Bridge Battle initiated three days of popular demonstrations and anti-government organization among soldiers in Budapest known collectively as the Aster Revolution, which compelled Archduke Joseph August to install Count Károlyi as prime minister in the name of the king on October 31.

Unknown assailants assassinated wartime prime minister István Tisza at his villa near the City Park in Pest on that same date, marking the only assassination of a major political figure in modern Hungarian history.

End of the War

Although Austro-Hungarian military forces remained active along the Italian Front when the Hungarian National Committee was formed on October 23, Emperor-King Charles and the entire Dual Monarchy political establishment had by this date recognized that the country would be forced to surrender to the Entente Powers within a matter of days or weeks. On October 17, even the pro-war former prime minister István Tisza publicly acknowledged this fact, declaring in Hungary’s House of Representatives “We have lost this war!”

On October 24, Entente armies launched the final offensive of the war along the Italian Front, compelling Austro-Hungarian forces to retreat from their defensive positions along the Piave River in what came to be known as the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. On October 29, an armistice delegation from the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs sued for peace on the Italian Front.

On November 1, Károlyi cabinet Minister of War Béla Linder ordered the Hungarian-recruited troops deployed on the Italian front to lay down their arms, fearing that the demoralized and mutinous soldiers, particularly those of non-Hungarian nationality, would rise up against the newly installed liberal-socialist government upon their return to Hungary.

On November 3, 1918, the Austro-Hungarian and Italian high commands signed a truce agreement known in English as the Armistice of Villa Giusti and in Hungarian as the Armistice of Padua [padovai fegyverszünet], thus signaling an end to the Dual Monarchy’s participation in the First World War.

End the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy

The majority of non-German and -Hungarian nationalities in Austria-Hungary had by the summer of 1918 come to advocate secession from the Dual Monarchy in order to join existing or nascent states to be either enlarged or wholly created from territory of the monarchy pursuant to the principle of national self-determination that U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s had proclaimed early that year.

On October 16, 1918, Emperor-King Charles issued a manifesto calling for the non-German nationalities in the Cisleithanian (Austrian) crown lands of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy to form their own national assemblies as the initial step in the transformation of this part of the Dual Monarchy into a federal state.

On October 29, the Croatian Sabor elected to secede from the Kingdom of Hungary and join the transitory State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. On October 30, the Slovak National Council also voted at an assembly in Turócszentmárton (Turčiansky Svätý Martin) to secede from the Kingdom of Hungary and join the incipient state of Czechoslovakia.

Moreover, the authority of the House of Habsburg and the Austrian and Hungarian political leaders and institutions that governed the Dual Monarchy disintegrated commensurately with that of Austro-Hungarian military resistance along the Italian front.

On November 11, 1918, Emperor-King Charles released the following statement:

I acknowledge the decision taken by German Austria to form a separate State. The people has by its deputies taken charge of the Government. I relinquish all participation in the administration of the State. Likewise I have released the members of the Austrian Government from their offices.

On November 12, the Imperial Council of Cisleithania proclaimed the foundation of the Republic of German-Austria in the German-inhabited regions of Austria and Bohemia under the leadership of Chancellor Karl Renner of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party.

Declaration of the First Hungarian Republic

After coming to power on October 31, the Károlyi government initially advocated elimination of all the formal political, military and economic links that had existed between Austria and Hungary during the Dual Monarchy era, though preservation of the personal union between the two countries under the Habsburg emperor-king.

However, following the apparent abdication of Emperor-King Charles and the proclamation of the Republic of German-Austria, the notion of maintaining the personal union under the Habsburg monarch no longer seemed feasible.

Therefore on November 13, 1918, a delegation of Hungarian nobles acting on behalf of the Károlyi government obtained the following declaration from King Charles at the Habsburg palace located in the village of Eckartsau, about 30 kilometers east of Vienna:

From this time on, I withdraw from all participation in the affairs of state and acknowledge in advance the decision that Hungary makes with regard to its future form of state.

On November 16, Prime Minister Károlyi and representatives of the Hungarian National Council proclaimed the establishment of the Hungarian People’s Republic—in retrospect the First Hungarian Republic—before a crowd of 200,000 supporters outside the Hungarian Parliament Building in Budapest.

Both the upper and lower houses of the National Assembly formally dissolved themselves on this same date, leaving the expanding Hungarian National Council to function as the sole legislative body in the newly established republic.

Károlyi Government Military Policy

The central objective of the Károlyi government was to distance the new Hungarian People’s Republic as much as possible from the Kingdom of Hungary that had fought the First World War on the side of the Central Powers as a means of earning as much goodwill as possible from the Entente Powers toward Hungary at the impending peace conference, particularly in order to gain full application of the Wilsonian principle of self-determination in the inevitable reconfiguration of the country’s borders.

The Károlyi government’s initial military policy was therefore based on pacifism and cooperation with the Entente Powers in the establishment and implementation of armistice conditions that would stabilize the borders of the new republic until the peace conference.

This initial policy of pacifism and compliance with the Entente is associated primarily with the Károly government’s first minister of war, Colonel Béla Linder, who served in the position from October 31 until November 9. Colonel Linder ordered the full demobilization of all Hungarian military units on November 1, declaring in a speech outside the Hungarian Parliament Building the following day that “We don’t need an army anymore! I never want to see another soldier again!” [Nem kell hadsereg többé! Soha többé katonát nem akarok látni!]

In early November, the Károlyi government concluded because the Armistice of Villa Giusti applied to the rapidly disintegrating Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in general and to the Italian Front specifically, it needed to sign a truce agreement in the name of Hungary alone that applied to the Balkan Front extending along the country’s southern border.

On November 13, Colonel Linder, by then serving as the Károlyi government’s minister without portfolio, signed an agreement in Belgrade with commanders from the armies of France and Serbia establishing a military demarcation line running across south-central Hungary in order to provide a buffer between Hungarian military forces and those from Serbia and Romania, which had reentered the war on the side of the Entente Powers on November 10, one day before Armistice of Compiègne ended the First World War.

The demarcation line stipulated in Belgrade Military Convention allowed troops from Serbia to occupy all of Croatia as well as most of the Bácska region in southern Hungary and troops from Romania to occupy southern and eastern Transylvania. The agreement specifically stipulated that Serbian and Romanian troops would not interfere in Hungary’s public administration of the occupied regions.

The Belgrade Military Convention permitted the Károlyi government to raise six infantry divisions and two cavalry divisions necessary to maintain public order.

General Albert Bartha, who succeeded Colonel Linder as the Károlyi government’s minister of war on November 9, recruited the eight divisions permitted in the Belgrade agreement through the enlistment of volunteers and the recall of recently demobilized soldiers between the ages of 18 and 22. General Bartha ordered the commanders of the newly raised divisions to defend Hungary’s national borders and military demarcation lines, thus signaling an end to the Károlyi government’s pacifist military policy.

However, General Bartha encountered resistance to his efforts from the Soldiers’ Council [Katonatanács] established to represent the interests of soldiers at the end of October 1918. Soldiers’ Council President József Pogány opposed the reenlistment of former officers to serve in the newly raised army as well as the suggested use of the military in a law-enforcement capacity alongside the police and gendarmerie. The increasingly socialist-revolutionary Soldiers’ Council staged a large demonstration in Budapest on December 12, 1918 that forced Bartha to resign from his position as minister of war and transfer his duties to Prime Minister Károlyi himself.

The Soldiers’ Council continued to act in opposition to the ministry of war during the entire period of the First Hungarian Republic.

Károlyi Government Domestic Policy

The Károlyi government attempted to implement a liberal-socialist domestic agenda via so-called people’s resolutions [néphatározat] stemming from the First Hungarian Republic’s legislative body, the Hungarian National Council, renamed the Great National Council [Nagy Nemzeti Tanács] after the council’s membership increased to more than five-hundred.

The Károlyi government enacted Great National Council resolutions extending the right to vote to all men over the age of 21 and all literate women over the age of 24, increasing suffrage to about 50 percent of the population in the Hungarian People’s Republic. The government also approved resolutions guaranteeing the freedoms of assembly, association and the press. In terms of social policy, the Károlyi government introduced unemployment benefits and prohibited the employment of children under the age of 14.

On February 16, 1919, the Berinkey government—which formed in the previous month following Prime Minister Károlyi’s resignation in order to formally assume the office of president of the republic—approved a Great National Council resolution calling for the redistribution, with compensation, of large private and Church-held estates to smallholders. However, implementation of this land reform extended only to President Károlyi’s redistribution of his own estate near the village of Kápolna, south of the city of Eger, before the collapse First Hungarian Republic in late March put an end to the Berinkey government’s initiative.

Károlyi government Nationality Affairs Minister Oszkár Jászi attempted to curb secessionist sentiment among non-Hungarian nationalities in Hungary by offering them autonomy within a federalized republic divided into largely self-governing cantons on the Swiss model. However, leaders of all the nationalities in Hungary with the exception of the Ruthenians (Ukrainians) living in the eastern part of the country rejected the notion of remaining in Jászi’s proposed “eastern Switzerland” rather than joining incipient and existing Czecho-Slovak, South Slav and Romanian nation-states.

Under Siege from Left and Right

The Károlyi and Berinkey governments operated under internal pressure from both the Party of Communists in Hungary on the left and the radical-nationalist Hungarian National Defense Association [Magyar Országos Véderő Egylet] on the right.

The Party of Communists in Hungary [Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja] formed in Budapest on November 24, 1918 under the leadership of Béla Kun, who like many of the founding members of the party had just returned to Hungary from the Russian Socialist Soviet Republic where they had become Marxist revolutionaries after falling into Russian captivity on the Eastern Front during the First World War. The newly founded Party of Communists in Hungary agitated openly against the Károlyi and Berinkey governments with the aim of fomenting proletarian revolution of the type that had brought the Vladimir Lenin-led Bolsheviks to power in Russia in November 1917.

The Berinkey government imprisoned Kun and other leaders of the Party of Communists in Hungary following a party-organized labor demonstration in Budapest on February 20, 1919 following which several demonstrators and policemen were killed in clashes outside the editorial office of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party newspaper Népszava.

The Hungarian National Defense Association, known as MOVE in its Hungarian-language acronym, formed under Staff Captain Gyula Gömbös in November 1918 with the objective of preventing the spread of communist ideology in Hungary and defending the country’s borders against foreign invasion. MOVE, which was composed primarily of Hungarian military officers, came to openly oppose the Károlyi and Berinkey governments as a result of their failure to achieve either of the organization’s main objectives. The Berinkey government banned MOVE in February 1919 due to the growing threat the organization posed to the internal security of the First Hungarian Republic.

Romanian and Czecho-Slovak Territorial Incursions

Military forces from the Kingdom of Romania transgressed the demarcation line defined in the Belgrade Military Convention with the permission of French General Henri Berthelot beginning in the middle of December, occupying the city of Koloszvár (Cluj in Romanian) on December 24. The Károlyi government elected not to resist this incursion, instead concluding a new agreement with General Berthelot through government commissioner István Apáthy on January 3, 1919 establishing a 15-kilometer buffer zone between Hungarian and Romanian military forces extending north and southwest of Kolozsvár. However, Romanian forces almost immediately advanced beyond this demilitarized zone as well in order to bring as much territory in the coveted region of Transylvania under its control before the impending start of the Paris Peace Conference.

The so-called Székely Division raised in Kolozsvár in December, 1918 opposed the newest unilateral violation of stipulated military demarcation lines, halting the Romanian advance at the historical border of Transylvania known in Hungarian as the Királyhágó [King’s Pass] on January 20 following minor skirmishes fought over the previous two weeks.

Czecho-Slovak military launched the occupation of Upper Hungary [Felvidék] on November 8, 1918, taking control of territory in the region of the cities of Trencsén (Trenčín) and Nagyszombat (Trnava) before newly appointed Károlyi government Minister of War Albert Bartha ordered Hungarian troops to resist further Czecho-Slovak advances three days later, thus temporarily halting the invasion.

On December 4, the head of the Entente military mission in Budapest, French Lieutenant-Colonel Fernand Vix, informed Prime Minister Károlyi that the French government would insist that the newly raised Hungarian military forces evacuate the predominantly Slovak-inhabited regions of Upper Hungary.

On December 6, Minister of War Bartha and former Hungarian National Assembly representative and president of the Slovak National Party Milan Hodža therefore concluded an agreement establishing a military demarcation line corresponding largely to the Hungarian-Slovak linguistic border in Upper Hungary. However, neither the Entente Powers nor Czecho-Slovak political leaders in Prague recognized the Bartha-Hodža demarcation line.

On December 23, Lieutenant-Colonel Vix ordered the Károlyi government to withdraw Hungarian troops further to “the historical boundaries of Slovakia,” including the predominantly Hungarian-inhabited lowland regions north of the Danube River as well as the cities of Pozsony (Bratislava) and Kassa (Košice). This new demarcation line conformed to that stipulated in an agreement concluded in Paris earlier that month between Czecho-Slovak Foreign Minister Edvard Beneš and French Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch.

Under pressure from multiple directions both internally and externally, the Károlyi government elected to comply with Lieutenant-Colonel Vix’s command rather than concentrating its resources on military resistance to the Czecho-Slovak occupation of Upper Hungary.

The Serbian army advanced beyond the Belgrade Military Convention-defined demarcation line extending through southern Hungary in December in order to occupy the Slovenian-inhabited Muraköz region, though otherwise complied with the stipulations of the agreement.

End of the First Hungarian Republic

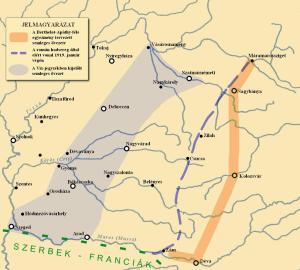

Purple field: neutral zone stipulated in March 20 Vix memorandum; purple dashed-line: extent of Romanian advance; orange line: neutral zone stipulated in January 3 Berthelot-Apáthy agreement.

The French-backed Czecho-Slovak and Romanian violation of stipulated military demarcation-lines and buffer-zones in December 1918 convinced Prime Minister Károlyi and the members of his cabinet to abandon their previous policy of pacifism and unqualified cooperation with the victorious Entente Powers.

In February 1919, Count Károlyi, by this time serving as president of the Hungarian republic, said: “We want to be prepared to regain our conditions of existence [létfeltétel] with weapons in our hands if we cannot do so on the basis of law and justice.”

On March 2, 1919, President Károlyi said in an address to units of the Székely Division in the city of Szatmárnémeti (Satu Mare in Romanian): “If all else fails, we will liberate this country by force. . . . If they want us to sign a peace agreement that entails the dismemberment of Hungary, then . . . I will not sign this agreement.”

On March 20, 1919, Lieutenant-Colonel Vix transmitted a memorandum to President Károlyi from the Paris Peace Conference calling upon the Berinkey government to withdraw Hungarian military forces a further 100 kilometers from the front that had emerged between the Hungarian and Romanian armies at the historical border of Transylvania in January to a line extending across the Great Hungarian Plain just beyond the city of Debrecen. The Berinkey cabinet rejected this demand from the leaders of the Entente Powers, electing instead to dissolve itself in order to allow President Károlyi to appoint a new government composed solely of ministers from the Hungarian Social Democratic Party, which maintained a greater degree of popular support and influence over the military than the two liberal parties in the governing coalition.

However, before President Károlyi could appoint this government, radical members of the Hungarian Socialist Democratic Party under the leadership of Hungarian National Council member Jenő Landler united with the Béla Kun-led Party of Communists in Hungary in order to form the Socialist Party of Hungary, which seized power from the Berinkey government on March 21 and proclaimed the establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic [Magyar Tanácsköztársaság].

President Károlyi, who had intended to remain head of state following the planned appointment of a new Hungarian Social Democratic Party cabinet, was compelled to acknowledge the socialist-communist putsch, though he insisted that his declaration of resignation published on March 22 was a forgery.

Mihály Károlyi: Villain and Hero

Mihály Károlyi lived in exile from shortly after the collapse of the First Hungarian Republic in 1919 until the establishment of the Second Hungarian Republic in 1946. During the intervening restoration of the Kingdom of Hungary under the leadership of Regent Miklós Horthy, the leading political figure of the First Hungarian Republic was held responsible for the subsequent “Red Terror” of the 133-day Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919 and the annexation of two-thirds of the territory of the Dual Monarchy-era Crown Lands of Saint Stephen via the Treaty of Trianon in 1920. In 1923, the state confiscated Count Károlyi’s remaining property in Hungary after a court convicted the former prime minister and president in absentia of treason and disloyalty. The Horthy government specifically accused Károlyi of acting against the interests of Hungary in his conclusion of agreements stipulating the withdrawal of Hungarian military forces from the country’s historical borders and his failure to defend even the military demarcation-lines stipulated in these agreements.

Communist officials unveil statue of Mihály Károlyi outside the Hungarian Parliament Building in 1975.

Mihály Károlyi returned from exile to participate in politics during the three-year Second Hungarian Republic. During this period, Károlyi cooperated with the Hungarian Communist Party, serving as the republic’s ambassador to France from 1947-1949. Károlyi was celebrated as the “red count” [vörös gróf] during the period of Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party rule under party General Secretary János Kádár beginning in the 1960s. In 1975, the Kádár government erected a statue of Mihály Károlyi on Kossuth Square outside the Hungarian Parliament Building in Budapest in recognition of his support for the Hungarian Social Democratic Party during the First Hungarian Republic and the Hungarian Communist Party during the Second Hungarian Republic.

The Fidesz-Christian Democratic People’s Party (KDNP) governing alliance and the radical-nationalist Jobbik party have largely revived the Horthy-era vilification of Mihály Károlyi since Fidesz-KDNP came to power in 2010.

Jobbik Vice-President Előd Novák places sign on statue of Mihály Károlyi: “I Am Responsible for Trianon.”

On June 3, 2010, Jobbik officials covered the statue of Mihály Károlyi next to the Hungarian Parliament Building with a black shroud, stating that their ultimate goal was to have the statue removed from the location. The Jobbik officials said that the site was not appropriate for a statue of somebody who had played a role in the “terror dictate” of the great powers following the First World War, referring to the Treaty of Trianon (source in Hungarian).

On July 11, 2011, the Fidesz-Christian Democratic People’s Party (KDNP) National Assembly alliance defeated a Jobbik-sponsored amendment to the bill on reconstruction of Kossuth Square calling for the removal of the Károlyi statue (source in Hungarian).

Fidesz National Assembly caucus Chairman János Lázár said he had voted against the proposal because he had not had the chance to consult with the artist who had sculpted the statue, Imre Varga (source in Hungarian).

On November 16, 2011, Jobbik president Gábor Vona referred to Mihály Károlyi as a “cheap, worthless historical fraud, the anti-Christ of 20th-century Hungary” [olcsó, ócska történelmi szélhámos, a húszadik századi Magyarország antikrisztusa] during a party demonstration at the statue of the former prime minister and president. Demonstrators later placed a kippah and a sign reading “I Am Responsible for Trianon” [Én Felelek Trianonért] on the statue (source in Hungarian).

Workers remove the statue of Mihály Károlyi from its site next to the Hungarian Parliament Building.

On March 26, 2012, Fidesz-KDNP and Jobbik members of the Budapest City Council voted to authorize the removal of the Mihály Károlyi statue from Kossuth Square and its placement in the city of Siófok on the south shore of Lake Balaton in central Hungary (source in Hungarian). Workers removed the statue from the square three days later, on March 29 (source in Hungarian).

The statue was erected in Siófok in September 2012 (source in Hungarian).

On December 11, 2012, the Fidesz-KDNP government issued a tender for a statue of Austro-Hungarian Monarchy-era Prime Minister István Tisza to be erected at the former location of the statue of Károlyi Mihály (source in Hungarian).

On April 25, 2013, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA) added Mihály Károlyi to the list of names in the “not recommended” category established pursuant to the 2011 law prohibiting the use of names associated with despotic political-systems to desginate public spaces in Hungary (source in Hungarian). The “not recommended” category is the most restrictive MTA classification for names of public spaces, below the “usable” and “usable, though with misgivings” categories.