The Second Hungarian Republic (1946–1949)

On January 31, 1946, National Assembly representatives approved a law proclaiming Hungary to be a republic, thereby abolishing—perhaps permanently—the Kingdom of Hungary that had existed since the year 1,000 with the exception of a sixteen-month period immediately following the First World War. The new republic was the second in Hungary’s history after that which had existed from November 1918 to March 1919 (see The First Hungarian Republic).

Independent representative Margit Slachta was the only member of the National Assembly who opposed the foundation of the Second Hungarian Republic, supporting Archbishop of Esztergom József Mindszenty’s proposal that legislators address the issue of Hungary’s form of government only after the process of post-war social and economic consolidation had been completed (source A and B in Hungarian).

Tildy Elected President

On February 1, 1946, National Assembly elected Independent Smallholders’ Party (FKgP) Prime Minister Zoltán Tildy by voice vote as president of the Second Hungarian Republic.

Many Independent Smallholders’ Party representatives had initially supported FKgP National Assembly Speaker Ferenc Nagy to serve as president of the new republic, while Civic Democratic Party representatives and some Hungarian Social Democratic Party representatives had endorsed First Hungarian Republic head of state Mihály Károlyi. However, the Hungarian Communist Party’s united support for Tildy effectively eliminated the possibility that either Nagy or Károlyi would gain sufficient backing in the National Assembly to be elected president, thus ending their brief candidacies (source A and B in Hungarian).

Following presidential vote, National Assembly Speaker Nagy publicly proclaimed the republic and announced the election of Tildy as head of state before an enormous crowd gathered outside the Hungarian Parliament Building in Budapest.

Formation of the Nagy Government

On February 4, 1946 the Independent Smallholders’ Party selected National Assembly Speaker Ferenc Nagy to replace Tildy as prime minister.

Prime Minister Nagy inherited a 16-member government that was composed of seven members of the Independent Smallholders’ Party, four members of the Hungarian Communist Party, four members of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party and one member of the National Peasant Party (source in Hungarian).

The National Assembly

At the time of the proclamation of the Second Hungarian Republic, Hungary’s National Assembly was composed of 409 elected representatives from the following five parties: the Independent Smallholders’ Party (59.9 percent of elected representatives); the Hungarian Communist Party (17.1 percent); the Hungarian Social Democratic Party (16.9 percent); the National Peasant Party (5.6 percent); and the Civic Democratic Party (0.5 percent).

At the time of the proclamation of the Second Hungarian Republic, Hungary’s National Assembly was composed of 409 elected representatives from the following five parties: the Independent Smallholders’ Party (59.9 percent of elected representatives); the Hungarian Communist Party (17.1 percent); the Hungarian Social Democratic Party (16.9 percent); the National Peasant Party (5.6 percent); and the Civic Democratic Party (0.5 percent).

The Independent Smallholders Party, the Hungarian Communist Party, the Hungarian Social Democratic Party and the National Peasant Party governed in a grand coalition that comprised 407 of the 409 elected representatives in the National Assembly, while the Civic Democratic Party represented the nominal opposition with just two representatives (see The Provisional National Government: 1945 National Assembly Election).

The Allied Control Commission

The Soviet-dominated Allied Control Commission (ACC) established in accordance with the January 1945 armistice agreement between the Provisional National Government and the Allied powers continued to exercise a significant influence over politics in Hungary following the proclamation of the Second Hungarian Republic (see The Provisional National Government: The Allied Control Commission). The ACC served as a powerful vehicle for the imposition of Soviet political control in Hungary via its support for the Hungarian Communist Party and the HCP-controlled Interior Ministry.

Execution of Wartime Government Officials

Between January and October 1946, The Budapest People’s Tribunal established under the Provisional National Government the previous year to prosecute war crimes imposed death sentences on 25 late interwar and wartime government officials, including: prime ministers Béla Imrédy (1938–1939), László Bárdossy (1941–1942) and Döme Sztójay (1944); Sztójay Government Interior Minister Andor Jaross and Interior Ministry state secretaries László Endre and László Baky; and Arrow Cross Party Government Nation Leader (Nemzetvezető) Ferenc Szálasi and 15 of the 19 ministers who served in his cabinets in 1944 and 1945 (source in Hungarian). The Budapest People’s Tribunal also extradited four Hungarian Royal Army and Hungarian Royal Gendarmerie officers to Yugoslavia, where they were tried and executed in November 1946 for their involvement in the Bácska Massacres of January 1942 (see The Horthy Era: The Bácska Massacres).

The 24 People’s Tribunals operating under the supervision of National Council of People’s Tribunals Chairman Ákos Major at the time of the Second Hungarian Republic issued 477 death sentences, of which 189 were carried out (source in Hungarian). A total of 150 of these death sentences were executed pursuant to verdicts from The Budapest People’s Tribunal (source in Hungarian).

Establishment of the Left-Wing Bloc

“Oust the Enemies of the People from the Coalition!” Rally marking the foundation of the Left-Wing Bloc.

On March 5, 1946, the Hungarian Communist Party, the Hungarian Social Democratic Party, the National Peasant Party and the Trade Union Council formed a political alliance called the Left-Wing Bloc (Baloldali Blokk). According to the Left-Wing Bloc’s program announced on the day of its formation, the main objectives of the alliance were: “to fight against the strengthening forces of reaction concentrated primarily in the right wing of the Independent Smallholders’ Party [and] against any attempt at the reactionary revision of land reform”; “to purge the state administration of reactionary civil servants”; and “to nationalize coal and bauxite mines, major heavy-industrial plants such as the Manfréd Weiss Steel and Metal Works and the Ganz factories and to place banks under direct state supervision” (source in Hungarian).

The Soviet-supported Left-Wing Bloc held its first mass demonstration in Budapest on March 7, 1946 under the slogan “Oust the Enemies of the People from the Coalition!”

The three Left-Wing Bloc parties commanded 39.6 percent of the seats in the National Assembly at the time of the alliance’s formation.

Expulsion of FKgP National Assembly Representatives from Party

On March 12, 1946, the Independent Smallholders’ Party announced the expulsion of 20 “reactionary” FKgP National Assembly representatives from the party in the hope that doing so would pacify the Left-Wing Bloc. The expulsions represented the first manifestation of the Hungarian Communist Party’s so-called “salami tactics”—the gradual elimination of all political opposition to communist rule as if cutting slices from a salami.

A few weeks later, 17 of the 20 National Assembly representatives expelled from the FKgP established the Hungarian Freedom Party (Magyar Szabadság Párt) under the leadership of Dezső Sulyok (source in Hungarian).

Law VII of 1946: Protection of the “Democratic State Order”

Also on March 12, the National Assembly adopted Law VII of 1946 “on the criminal-law protection of the democratic state order and the republic.”

This law criminalized “actions, movements or organizations aimed at overthrowing the democratic state order or the democratic republic.” (source in Hungarian).

Only the two-member Christian-socialist faction of the FKgP and the independent Christian-socialist representative Margit Slachta opposed the law, the latter insisting that the legislation specifically state that it would be applied only to “unlawful” actions, movements and organizations (source in Hungarian).

This law, which opponents dubbed the “executioner’s law” (hóhértörvény), was frequently used as the legal grounds to prosecute defendants in show trials held in Hungary in the years 1946–1953.

Dismissal of “B-List” State Employees

In May 1946, the Nagy cabinet issued a resolution calling for each government ministry to conduct a ten-percent reduction in personnel in order to reduce budgetary expenditures and to remove employees who inhibited Hungary’s “democratic restructuring.” The resolution established a committee to compile a “B-list” identifying the ministry personnel to be dismissed based on information from the Left-Wing Bloc-affiliated Trade Union Council. Around 60,000 B-listed ministry personnel were dismissed over the subsequent months and around 20,000 more over the following two years, many of them because the communist-controlled Trade Union Council had determined them to be “reactionary” (source A and B in Hungarian).

Banning of Christian-Nationalist Organizations

On June 17, 1946, two Red Army officers were shot and killed near the Oktogon square in Budapest. Officials concluded that a 17-year-old Hungarian, whose corpse was discovered in a nearby building along with papers identifying him as a member of the Roman Catholic agrarian youth-organization KALOT, had committed the murders.

The Soviet deputy chairman of the Allied Control Commission charged during a late-June meeting with Prime Minister Nagy that members of KALOT, the Hungarian Scout Federation (Magyar Cserkészszövetség) and other Christian-nationalist youth organizations had been responsible for the assassination of 50 Red Army soldiers in Hungary over the previous six months, demanding in a subsequent letter that these “pro-fascist” organizations be banned (source A and B in Hungarian).

Prime Minister Nagy therefore transferred the sole authority to oversee the operations of such organizations to Hungarian Communist Party Interior Minister László Rajk, who dissolved both KALOT and the Hungarian Scout Federation on July 4, 1946 and 1,450 other Christian-nationalist organizations by the end of the year (source in Hungarian)

Expulsion of Germans from Hungary

In July 1945, leaders from the Soviet Union, the United States and the United Kingdom met in the city of Potsdam, just outside Berlin, to discuss issues regarding the post-war administration of Germany, Axis Power war reparations and the status of Germans living in Eastern Europe. According to an agreement signed during the conference, “The Three Governments . . . recognize that the transfer to Germany of German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, will have to be undertaken.”

Allied Control Commission Chairman Kliment Voroshilov and other Soviet ACC officials subsequently demanded that the government of Hungary initiate the expulsion of 450,000 to 500,000 citizens of German nationality to Germany (source in English).

The main motives of the major Allied Powers for initiating the expulsion of Germans from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary was to avert potential political upheaval connected to the presence of large German-minority populations in these states.

National Assembly parties in Hungary were divided regarding the issue of expelling Germans form the country: officials from the Independent Smallholders’ Party and the Hungarian Social Democratic Party tended to reject the proposed expulsion of Germans on the grounds that it would provide the governments of neighboring countries with a pretext for expelling Hungarians in the same manner, while officials from the pro-Soviet Hungarian Communist Party and the National Peasant Party supported the proposed expulsion of Germans in compliance with the request of the Allied Control Commission (source in English). Moreover, many political officials from Hungary advocated expelling Germans in order to provide housing and economic opportunity for some of the more than 300,000 Hungarians who had fled to the country from neighboring states at the end of the war (source in Hungarian).

According to official statistical data compiled in Hungary in October 1945, around 477,000 citizens of the country spoke German as their native language—a number that included many Jews—while 303,000 were of German nationality (source in English).

In December 1945, the Tildy government adopted a resolution regarding “the transfer of the German population of Hungary to Germany” pursuant to the “decree of the Allied Control Commission” (source in Hungarian).

This resolution called for the expulsion to Germany of all Hungarian citizens who in the 1941 census had declared themselves to be of German nationality or of German native language or who had been members of the Volksbund—the banned pro-Nazi organization of the Germans of Hungary—or the Hungarian divisions of the Waffen-SS. The resolution provided exemptions to minors and those over 65 years of age as well as those who had been active in one of the “democratic” parties (i.e., the post-war Provisional National Government and Tildy government parties). The resolution stipulated the immediate confiscation of all moveable and non-moveable property belonging to those subject to expulsion.

The expulsion of Germans from Hungary began by train from Budaörs (Wudersch) and other towns surrounding Budapest on January 19, 1946 and continued until June 1948. Over that two-and-a-half-year period, an estimated 180,000 Hungarians citizens of German nationality were expelled to Germany—around 145,000 to the U.S. Occupation Zone and 35,000 to the Soviet Occupation Zone (source in Hungarian).

Nationalization of Coal Mines and Major Industrial Enterprises

In 1946, the National Assembly nationalized all coal mines in Hungary as well as four major industrial enterprises in the country—the Ganz machine factories in Budapest, the Manfréd Weiss Steel and Metal Works in nearby Csepel, the Győr Wagon and Machine Factory and the Rimamurány-Salgótarján Iron Works (source in Hungarian).

The nationalization of coal mines and the above companies and their subsidiaries increased the number of people working in the state-owned industrial sector from 10 percent of all industrial workers at the beginning of 1946 to 43 percent of all industrial workers at the end of 1946 (source in Hungarian).

The Czechoslovak-Hungarian Population Exchange

A Hungarian bids farewell to his Slovak neighbor in the village Guta (Gúta) during the summer of 1947 before leaving for Hungary as part of the Czechoslovak-Hungarian population exchange.

Following the Second World War, the government of Czechoslovakia acting under the authority of President Edvard Beneš sought to expel the minority populations of over 2.5 million Germans and a half million Hungarians from the country on the grounds that they had supported the dismemberment of the First Czechoslovak Republic in the years 1938–1939 and therefore posed a threat to state unity.

In August 1946, President Edvard Beneš issued a decree revoking the Czechoslovak citizenship from all those who had declared themselves to be of German or Hungarian nationality in the 1930 census or had become citizens of Germany or Hungary after the incorporation of Czechoslovak territories into these countries in 1938 and 1939.

However, officials from the United States and the United Kingdom rejected the Czechoslovak government’s proposed unilateral expulsion of Hungarians from Slovakia at both the Potsdam Conference and the Paris Peace Conference in the summer and autumn of 1945, respectively (source in Hungarian). Therefore, the Czechoslovak government of Prime Minister Klement Gottwald initiated talks with the Nagy government regarding the exchange of Hungarians living in Slovakia for Slovaks living in Hungary, of which there was an underreported total of just over 75,000 according to the 1941 Hungarian census (source in Hungarian).

On February 27, 1946, Deputy Foreign Minister Vladimír Clementis of Czechoslovakia and Foreign Minister János Gyöngösi of Hungary signed an agreement in Budapest stipulating the exchange of Hungarians from Slovakia for Slovaks from Hungary. According to the agreement, the government of Czechoslovakia could expel the same number of Hungarians from Slovakia as the number of Slovaks who voluntarily resettled from Hungary to Slovakia (source in Hungarian). The Slovak-for-Hungarian population exchange began just over one year later—in April 1947—and essentially ended in in December 1948, though a few Hungarians chose to leave Slovakia within the framework of the agreement during the first half of the following year. Over this time, 60,257 Slovaks moved from Hungary to Slovakia and 76,616 Hungarians moved from Slovakia to Hungary according to the terms of the population-exchange agreement (source in Hungarian).

Hyperinflation and Introduction of the Forint

Price inflation began to increase rapidly in Hungary during the summer of 1945 as a result of sharply declining production due to the destruction of infrastructure in the country in bombing and ground combat during the final year of the Second World War.

The cost of one kilogram of bread, for example, increased from six pengő in August 1945 to eight million pengő in May 1946 and to nearly six billion pengő on month later. The Dálnoki Miklós, Tildy and Nagy governments printed the national currency in ever larger denominations in a counterproductive effort to curb inflation, eventually issuing a 100 million billion pengő note. Inflation reached a single-day high of 348.46 percent on July 10, 1946—an all-time record that lasted for many decades (source in Hungarian).

On August 1, 1946, the Nagy government introduced the forint to replace the essentially valueless pengő, thus putting an end to hyperinflation in Hungary.

Foundation of the ÁVO Political Police

Hungarian Communist Party Interior Minister László Rajk oversaw the establishment of the State Protection Department (Államvédelmi Osztály, or ÁVO) political-police force in October 1946. Acting under the direction of longtime labor-movement activist Gábor Péter, The ÁVO essentially functioned as an instrument of the HCP, subverting rival parties through the arrest of their supporters and officials and promoting communist domination of the Second Hungarian Republic.

Suppression of the Hungarian Fraternal Community

The Hungarian Fraternal Community (Magyar Testvéri Közösség) was a secretive nationalist organization established in Hungary during the interwar period to serve as a forum for activities intended to strengthen the Hungarian nation and rebuild fractured Hungarian national unity.

Following the Second World War, most of the few thousand members of the Hungarian Fraternal Community gravitated politically toward the Independent Smallholders’ Party, including several who became FKgP officials and National Assembly representatives.

In December 1946, the communist-controlled ÁVO political police began arresting members of the Hungarian Fraternal Community on charges of “anti-republic conspiracy” as a means of subverting both the organization as well as the FKgP. The ÁVO eventually arrested 260 people suspected of involvement in this conspiracy, including Nagy government Minister of Construction and Public Work Endre Mistéth and seven Independent Smallholders’ Party National Assembly representatives following the withdrawal of their parliamentary immunity (source A and B in Hungarian).

However, the relevant National Assembly committee refused to revoke the parliamentary immunity of Independent Smallholders’ Party First Secretary Béla Kovács. Therefore, on February 25, 1947, Soviet authorities arrested Kovács on charges of organizing “underground anti-Soviet groups” and deported him to the Soviet Union, where he was sentenced to 20 years in prison (source A and B in Hungarian)

Between April 1947 and March 1948, the Budapest People’s Tribunal condemned 12 people, including Mistéth and five of the seven arrested FKgP National Assembly representatives, to between three and 15 years in prison and leading Hungarian Fraternal Community figure György Donáth to death for complicity in the “conspiracy against the republic” (source in Hungarian).

The Paris Peace Treaty

On February 10, 1947, representatives from the Allied Powers and the European Axis Powers other than Germany—Italy, Hungary, Finland, Romania and Bulgaria—concluded peace treaties in Paris formally ending the state of war that had existed between them since the years 1939–1941.

The peace treaty that Nagy government Foreign Minister János Gyöngyosi signed with representatives from the four major Allied Powers, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia reinstated the borders of Hungary stipulated in the 1920 Treaty of Trianon with one exception: a modest enlargement of the so-called Bratislava Bridgehead south of the Danube River just below the city in order to reduce its exposure to attack from Hungary (source in Hungarian). This 62-square-kilometer territory included three villages of mixed Hungarian, German, Croat and Slovak nationality— Oroszvár (Rusovce), Horvátjárfalu (Jarovce) and Dunacsún (Čunovo).

The Treaty of Peace with Hungary also confirmed the stipulation in the Provisional National Government’s January 1945 armistice with the Allied powers requiring the country to pay 300 million U.S. dollars in war reparations—200 million to the Soviet Union, 70 million to Yugoslavia and 30 million to Czechoslovakia.

The treaty specified, moreover, that “Hungarian prisoners of war shall be repatriated as soon as possible in accordance with arrangements agreed upon by the individual powers detaining them and Hungary” (source in English).

Finally, the treaty stipulated that all Allied forces must be withdrawn from Hungary within 90 days “subject to the right of the Soviet Union to keep on Hungarian territory such armed forces as it may need for the maintenance of the lines of communication of the Soviet Army with the Soviet zone of occupation in Austria” (source in English). This clause enabled the Soviet Union to maintain a significant military presence in Hungary following the conclusion of the treaty.

The Treaty of Peace with Hungary came into effect on September 15, 1947, at which time the Allied Control Commission founded to oversee the country’s compliance with the 1945 armistice agreement dissolved itself.

Repatriation of Hungarian POWs

The Red Army deported between 360,000 and 400,000 Hungarian Royal Army soldiers and between 200,000 and 240,000 civilians of Hungarian nationality to labor camps in the Soviet Union from September 1944 until the middle of 1945 (source A in Hungarian and B in English).

A further 300,000 Hungarian Royal Army soldiers fell into U.S., British and French captivity in the spring of 1945 (source in English). All of these soldiers returned to Hungary by the summer of 1946 (source in Hungarian).

Soviet officials began authorizing the release of Hungarian prisoners of war only after the conclusion of the Treaty of Peace with Hungary in February 1947, repatriating 100,288 Hungarian POWs by the end of the latter year, 84,310 in 1948 and around 215,000 more over the subsequent few years (source A and B in Hungarian).

Therefore, around one-third of the roughly 600,000 Hungarian Royal Army soldiers and civilians of Hungarian nationality that the Red Army deported to the Soviet Union in 1944 and 1945 never returned to Hungary and are presumed to have died in captivity (source in Hungarian).

Forced Resignation of Prime Minister Nagy

On May 14, 1947, Prime Minister Nagy traveled to Switzerland under the pretext of spending his summer holiday in the country, but in fact to take temporary shelter from the increasingly intense subversion of the Hungarian Communist Party (source A and B in Hungarian).

Two weeks later, the ÁVO arrested Nagy’s personal secretary on fabricated charges, while HCP General Secretary Mátyás Rákosi informed the prime minister via telephone that the Allied Control Commission had provided the government with evidence of his complicity in an “anti-state conspiracy” (see: Ignác Romsics, Hungary in the Twentieth Century).

On May 30, the Hungarian News Agency MTI spuriously announced that Prime Minister Nagy had submitted his resignation. The following day, Independent Smallholders’ Party Defense Minister Lajos Dinnyés, who maintained friendly relations with high-ranking Hungarian Communist Party officials, was appointed to replace Nagy as prime minister.

On June 1, Nagy resigned from his post as prime minister after his family was permitted to join him in Switzerland, from where they emigrated permanently to the United States.

Establishment of the National Planning Office and the First Three-Year Plan

The National Assembly established the National Planning Office (Országos Tervhivatal) in June 1947 to devise government economic policy and oversee its implementation. Under the leadership of Hungarian Social Democratic Party representative Imre Vajda, the National Planning Office formulated Hungary’s Three-Year Plan launched in August 1947 (source in Hungarian). This centralized economic plan based on the Soviet model was aimed at “reconstruction and revival of the Hungarian economy afflicted by war damage and destruction” (source in Hungarian).

Adoption of New Suffrage Law

On July 23, 1947, the National Assembly approved a new, Hungarian Communist Party-instigated suffrage law that contained three important amendments to the previous suffrage law adopted a few months after the Second World War (sources A and B in Hungarian):

first, the new law authorized voters to cast their ballots at polling places anywhere in Hungary, thus abolishing the previous requirement that they vote at the designated polling place in their home electoral-district;

second, the law stipulated that 80 percent of the 60 mandates awarded via national party-lists would be granted proportionally to the four parties in the existing government-coalition in the event that they collectively received at least 60 percent of all votes cast;

and third, the law disqualified those who had served as parliamentary representatives for the parties that had governed Hungary from 1935 to 1944—the Party of National Unity (Nemzeti Egység Pártja) and the Party of Hungarian Life (Magyar Élet Pártja)—from standing as candidates in National Assembly elections.

The primary purpose of the latter amendment, which was known informally as the “Lex Sulyok,” was to prevent Dezső Sulyok and other leaders of the increasingly popular anti-communist Hungarian Freedom Party who had served as parliamentary representatives in the stipulated governing parties between 1935 and 1944 from running in National Assembly elections (source in Hungarian).

The Sulyok-led Hungarian Freedom Party dissolved itself on July 21 to protest the impending new suffrage law.

Formation of the Hungarian Independence Party

On July 26, 1947, National Assembly representatives expelled from the FKgP earlier in the year—including those who had been part of the Hungarian Freedom Party dissolved three days previously—founded the Hungarian Independence Party (Magyar Függetlenségi Párt) under the leadership of Zoltán Pfeiffer (source in Hungarian).

The Hungarian Independence Party’s published program stated (source in Hungarian):

The Hungarian Independence Party stands on national and civil foundations and proclaims the principle of Gospel-based socialism and personal freedom. We are a worldview party that, in contrast to Marxist materialism and collectivism, professes the preeminence of the individual, the human soul, morality and free, individual creative force.

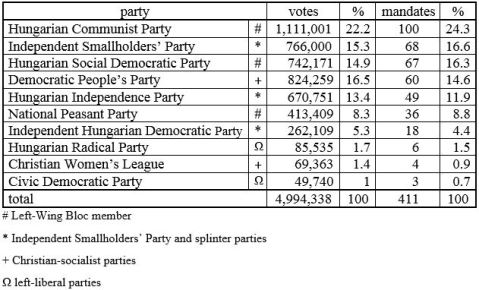

The 1947 “Blue-Slip” National Assembly Election

In late July 1947, the National Assembly voted to dissolve itself under pressure from the parties of the Left-Wing Bloc and President Zoltán Tildy called a general election to be held on the final day of August.

Ten parties contested the National Assembly election held in Hungary on August 31, 1947:

the three Left-Wing Bloc parties—the Hungarian Communist Party, the Hungarian Social Democratic Party and the National Peasant Party;

the Independent Smallholders’ Party;

the Hungarian Independence Party and another newly formed FKgP splinter party—the centrist Independent Hungarian Democratic Party (Független Magyar Demokrata Párt) under the leadership of Roman Catholic priest István Balogh;

the left-liberal Civic Democratic Party (Polgári Demokrata Párt) and Hungarian Radical Party (Magyar Radikális Párt) that had participated in the 1945 general election, though had together received less than two percent of the vote;

the István Barankovics-led Christian-socialist Democratic People’s Party (Demokrata Néppárt);

and the Margit Slachta-led Christian Women’s League (Keresztény Női Tábor).

On the day of the election, the Hungarian Communist Party conducted large-scale electoral fraud, distributing tens of thousands of forms, known as “blue slips” due to the color of the paper on which they were printed, authorizing citizens to vote outside their home electoral district to party activists, who travelled by bus, passenger vehicle and even bicycle to cast ballots at multiple polling places. According to ÁVO director Péter Gábor, HCP activists cast around 62,000 multiple votes, though historians estimate that the actual number of such votes may have ranged between 120,000 and 200,000 (source A and B in Hungarian).

This fraud helped the Hungarian Communist Party win this so-called “blue-slip” election with slightly more than 1.1 million votes—nearly 287,000 more than the party that gained the second-highest number of votes, the Democratic People’s Party. The final election results:

Because the four parties from the previous governing coalition—the Independent Smallholders’ Party, the Hungarian Communist Party, the Hungarian Social Democratic Party and the National Peasant Party—together won 60.7 percent of the vote, they gained 48 of the 60 mandates granted via national party-lists in accordance with the amendment to the Suffrage Law stipulating that coalition parties would proportionally receive 80 percent of all party-list mandates if they collectively received at least 60 percent of all votes cast. As a result of this amendment, the six parties participating in the election that were not part of the previous governing coalition—none of which were members of the Left-Wing Bloc—obtained only 34.1 percent of all National Assembly mandates on 39.3 percent of the vote. This so-called “premium system” was particularly harmful to the Democratic People’s Party, which gained only the fourth-highest number of mandates in the new National Assembly despite winning the second-highest number of votes in the general election.

Although the non-Left-Wing Bloc parties together had won enough National Assembly mandates to form a new government, the Independent Smallholders’ Party—which communist “salami tactics” had largely divested of its Christian-nationalist elements—chose to again form a coalition with the Hungarian Communist Party, the Hungarian Social Democratic Party and the National Peasant Party under FKgP Prime Minister Lajos Dinnyés.

The 15-member government that Dinnyés formed on September 24, 1947 was composed of five ministers from the Hungarian Communist Party, four ministers from the Independent Smallholders’ Party and three ministers each from the Hungarian Social Democratic Party and the National Peasant Party.

Suppression of the Hungarian Independence Party

In October 1947, the four government-coalition parties and the opposition Hungarian Radical Party submitted a petition to the National Election Committee (Országos Választási Bizottság) requesting that the electoral results of the Hungarian Independence Party be annulled on the grounds that the FKgP successor party had forged signatures on around one-quarter of the recommendations required to participate in the National Assembly election held a few weeks earlier (source in Hungarian).

Also during this month, the Hungarian Communist Party-controlled ÁVO launched an investigation of Hungarian Independence Party National Assembly representative and President Zoltán Pfeiffer on charges of “conspiracy.”

On November 4, 1947, the relevant National Assembly committee voted to revoke Pfeiffer’s parliamentary immunity. The Hungarian Independence Party leader therefore fled from Hungary to Austria in order to avoid arrest and went into exile in the United States.

On November 20, 1947, the Left-Wing Bloc-dominated National Election Committee voted to invalidate the National Assembly election results of the Hungarian Independence Party, thus depriving the party of its 49 parliamentary representatives. On this same date, Interior Minister László Rajk dissolved the Hungarian Independence Party.

The annulment of the Hungarian Independence Party’s election results reduced the number of representatives in the National Assembly from 411 to 362 and transformed the 49.4-percent relative majority of Left-Wing Bloc representatives in parliament into a 56.1-percent absolute majority.

Károly Peyer Forced into Exile

Longtime Hungarian Social Democratic Party National Assembly faction leader and representative Károly Peyer represented one of the most vociferous opponents of closer cooperation between the HSDP and the Hungarian Communist Party during the immediate post-Second World War period. The pro-HCP wing of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party therefore orchestrated Peyer’s dismissal from his party offices during the HSDP congress that began in January 1947. Peyer thus withdrew from the Hungarian Social Democratic Party and gained reelection to the National Assembly as a candidate of the Hungarian Radical Party in August 1947. The Left-Wing Bloc-controlled National Assembly voted to revoke Peyer’s parliamentary immunity in November 1947 so that he could be brought to trial on charges of conspiracy and espionage. However, Peyer fled from Hungary on November 19, 1947 to avoid arrest and settled in the West, first in France, then in the United States (source in Hungarian).

The Budapest People’s Tribunal subsequently found Peyer guilty in absentia of the stated charges and sentenced him to eight years in prison (source in Hungarian).

Nationalization of Banks and Bauxite and Aluminum Enterprises

In late November 1947, the National Assembly adopted a law nationalizing the National Bank of Hungary (NBH) and the eight major private-sector banks operating in the country and introduced a one-level banking system in which the NBH played the role of both central bank and commercial bank (source in Hungarian).

During this same month the National Assembly passed a law nationalizing enterprises engaged in the bauxite and aluminum industries (source in Hungarian). The latter measure increased the number of people working in the state-owned industrial sector to 50 percent of all industrial workers (source in Hungarian).

The Hungarian-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance

On February 18, 1948, Prime Minister Lajos Dinnyés of Hungary and Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov of the Soviet Union signed the Hungarian-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance in Moscow (source in Hungarian). The nominal objective of this treaty was to establish the framework for mutual Hungarian-Soviet defense against revived German aggression. The actual objective of the treaty was to prevent Hungary from joining a potential anti-Soviet political-military alliance (source in Hungarian).

Expulsion of “Right-Wing” Hungarian Social Democratic Party Officials

On February 18, 1948, Hungarian Social Democratic Party leader György Marosán announced the expulsion of 40 people, including Deputy Speaker of the National Assembly Anna Kéthly, Industrial Affairs Minister Antal Bán and HSDP Deputy General Secretary Ferenc Szeder, from the party for engaging in “unity-undermining and worker-betraying politics” (source in Hungarian). The true purpose of the Hungarian Communist Party-instigated expulsion of these “right-wing” Hungarian Social Democratic Party officials was to remove internal obstacles to the unification of the HCP and the HSDP (source in Hungarian).

Nationalization of Factories Employing over 100 Workers

On March 25, 1948, the Dinnyés Government issued a decree nationalizing all factories in Hungary that employed over 100 workers (source in Hungarian). The National Assembly elevated this resolution to law six weeks later (source in Hungarian). As a result of this measure, the number of people working in the state-owned industrial sector to 84 percent of all industrial workers (source in Hungarian).

The Nitrokémia Show Trial

In March 1948, the Budapest People’s Tribunal tried the directors of the Nitrokémia gunpowder, explosives and chemical company on charges of conspiracy. The purpose of the Hungarian Communist Party-orchestrated trial was to further discredit the “right-wing” of Hungarian Socialist Democratic Party with which the directors of Nitrokémia were associated (source in Hungarian).

On March 4, the court sentenced Nitrókémia CEO Kornél Szabó to death and three other company directors—former HSDP Industrial Affairs Ministry State Secretary Gyula Kelemen, former HSDP Defense Ministry State Secretary József Sárkány and Lajos Steller—to life in prison after finding them guilty of “misusing company credit” and “putting important reports and company plans in the hands of Horthyists and foreigners” (source A and B in Hungarian).

Former Nitrókémia CEO Szabó was executed in September 1948 after the National Council of People’s Tribunals upheld the verdicts.

Formation of Civic Radical Party Alliance

Poster proclaiming the unification of the Hungarian Communist Party and the Hungarian Social Democratic Party.

In May 1948, the left-liberal Civic Democratic Party and Hungarian Radical Party, which had together won 2.7 percent of the vote and 9 National Assembly mandates in the “blue-slip election” the previous summer, united as the Civic Radical Party Alliance (Polgári Radikális Pártszövetség). The parties retained their formal independence within this alliance until the spring of 1949, when the Civic Democratic Party merged into the Hungarian Radical Party (source in Hungarian).

Foundation of the Hungarian Workers’ Party

On June 12, 1948, the Hungarian Communist Party and Hungarian Social Democratic Party held joint congresses in Budapest at which delegates voted to merge the parties into the Hungarian Workers’ Party (Magyar Dolgozók Pártja). HCP leader Mátyás Rákosi was named general secretary of the Hungarian Workers’ Party, while HSDP leader Árpád Szakasits was named president of the new party (source A and B in Hungarian).

Nationalization of Parochial Schools

On June 16, 1948, the National Assembly approved a law nationalizing the 6,505 Church-operated schools in Hungary (source in Hungarian). Nearly half of these schools belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, while most of the rest belonged to the Reformed and Lutheran Churches (source in Hungarian).

The Pócspetri Show Trial

A police officer in Pócspetri (eastern Hungary) sustained an accidental self-inflicted mortal wound from his own gun on June 3, 1948 as he attempted to prevent Parish Priest János Asztalos and members of his congregation from gaining access to a meeting of the village council in order to protest the nationalization of the local Catholic school (source in Hungarian). Hungarian Communist Party officials exploited the incident to hold a show trial exposing “clerical reaction,” orchestrating the immediate hearing of Asztalos and alleged accomplices before the Budapest People’s Tribunal. The court condemned Pócspetri notary Miklós Királyfalvi to death and Reverend Asztalos to life in prison after finding them guilty of murder and incitement to murder, respectively, at the end of the highly publicized trial on June 11, 1948. Királyfalvi was executed later on the same date (source in Hungarian).

Szakasits Succeeds Tildy as President of the Republic

The leadership of the Hungarian Workers’ Party (HWP) decided shortly after its foundation to remove President Zoltán Tildy of the Independent Smallholders’ Party from office. In order to achieve this objective, the ÁVO arrested Tildy’s son-in-law, Viktor Csornoky, on July 23, 1948 on charges that he had committed treason while serving as Hungary’s ambassador to Egypt over the previous months. The HWP used the arrest of Csornoky to compromise and further weaken Tildy, who resigned as president of the republic on July 31, 1948. Three days later, the National Assembly elected HWP President Árpád Szakasits to succeed Tildy as head of state.

Zoltán Tildy was placed under house arrest immediately following his resignation. Viktor Csornoky was executed on December 7, 1948 after the Budapest People’s Tribunal found him guilty of espionage at the conclusion of a show trial.

The Hungarian-American Oil Company Show Trial

Defendants stand before the Budapest People’s Tribunal during the Hungarian-American Oil Company trial.

In August and September 1948, the ÁVO arrested several Hungarian-American Oil Company officials, including recently retired CEO Simon Papp, on charges of economic sabotage. Hungarian Workers’ Party leaders engineered the arrests primarily in order to gain state control over the concern, a subsidiary of the U.S. Standard Oil Company that engaged in petroleum exploration and extraction in Hungary. The arrest of Papp and his former associates also served the HWP’s propaganda objective of divulging an alleged U.S.-directed imperialist conspiracy to undermine Hungary’s economy (source in Hungarian).

Following a two-week show trial beginning in November 1948, the Budapest People’s Tribunal condemned Papp to death and Hungarian-American Oil officials Ábel Bódog and Béla Binder to 15 years and 4 years in prison, respectively, after having found them guilty of conspiracy to subvert the company’s operations. The court subsequently commuted Papp’s sentence to life in prison (source in Hungarian).

Reorganization of the Political Police: Foundation of the ÁVH

The Interior Ministry reorganized the ÁVO following the appointment of Hungarian Workers’ Party Deputy General Secretary János Kádár to succeed László Rajk as Interior Minister in August 1948, changing the name of the political police-force from the State Protection Department to the State Protection Authority (Államvédelmi Hatóság, or ÁVH) and transferring the prerogative to patrol the borders of Hungary, monitor the activities of foreigners residing in the country and issue passports to Hungarian citizens from the regular police to this new organization. The official establishment of the State Protection Authority via Interior Ministry decree on September 10, 1948 also increased the authority of ÁVH director Péter Gábor, providing him with the independent power to order the expulsion, police supervision and arrest of individuals considered harmful to state security (source in Hungarian).

Imprisonment of Lutheran Bishop Lajos Ordass

On October 1, 1948 the Budapest Usury Court sentenced Lutheran World Federation Vice President Bishop Lajos Ordass to two years in prison after finding him guilty of spurious charges that he had failed to report nearly 300,000 dollars in financial assistance obtained during a visit to the United States the previous year to the Hungarian National Bank in accordance with foreign-currency law (source A and B in Hungarian).

Dobi Replaces Dinnyés as Prime Minister

Hungarian Workers’ Party officials forced Independent Smallholders’ Party Prime Minister Lajos Dinnyés to resign on December 10, 1948 after his cabinet’s finance minister, Miklós Nyárádi, announced while on a visit to the West that he would not return to Hungary, claiming that this defection indicated that Dinnyés was unfit to lead the government. FKgP Minister of Agricultural Affairs István Dobi, a communist sympathizer, was appointed to replace Dinnyés. Prime Minister Dobi made only the required changes to the previous government, appointing HWP Transportation Minister Ernő Gerő to serve as interim finance minister and naming a fellow Independent Smallholders’ Party member to succeed him as minister of agricultural affairs.

Laying the Foundation for the Collectivization of Agriculture

Hungarian Communist Party leaders had been reluctant to initiate the collectivization of agriculture following the Second World War, fearing that nationalizing arable land and forcing farmers to join cooperatives might provoke violent rebellion in rural areas of Hungary as had occurred at the time of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919 (source in English). However, the expulsion of Yugoslavia from the Communist Information Bureau (Cominform) in June 1948 based partially on the grounds that the Tito government had failed to collectivize agriculture in the country prompted HWP officials to place this issue on the party agenda.

Hungarian Workers’ Party General Secretary Mátyás Rákosi first publicly suggested that agriculture would be collectivized in Hungary during a speech in August 1948 in which he claimed that “the working peasantry has chosen cooperation, mutual assistance and common work . . . in place of old, established, excessively individual farming” (source in Hungarian). Rákosi also initiated the HWP’s anti-kulak campaign during this speech, declaring that “democracy ensures that the tree of the major kulak farmer does not grow to the skies, that the expansion of kulaks remains within limits” (source in Hungarian).

On December 18, 1948, the Dobi Government issued a decree establishing three classifications of agricultural cooperative—two transitional categories in which farmers could retain some of their private holdings and one permanent category in which they would yield all their private holdings except that surrounding their houses.

However, collectivization of agriculture proceeded very slowly following the introduction of the cooperative system: by the summer of 1949, only around 13,000 farmers had joined 584 cooperative groups in Hungary (source in Hungarian).

Establishment of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance

In early January 1949, Dobi Government Finance Minister Ernő Gerő and representatives from five other countries in Eastern Europe—the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Bulgaria—signed an agreement establishing the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon) at the conclusion of a three-day meeting in Moscow. The January 8 agreement stated that the signatories had founded Comecon “in view of establishing broader economic cooperation between the people’s democracies and the Soviet Union . . . since these countries do not consider it possible to subordinate themselves to the dictates of the Marshall Plan” (source in English).

Formation of the Hungarian Independent People’s Front

On February 1, 1949, the three governing parties—the Hungarian Workers’ Party, the Independent Smallholders’ Party and the National Peasant Party—and three* of the five remaining opposition parties united as distinct entities in the Hungarian Independent People’s Front (Magyar Függetlenségi Népfront) under the presidency of HWP General Secretary Rákosi. The formation of the Hungarian Independent People’s Front reduced the National Assembly opposition to only two Christian-socialist parties that together had won slightly less than 18 percent of the vote in the 1947 general election: the István Barankovics-led Democratic People’s Party and the Margit Slachta-led Christian Women’s League (source in Hungarian).

*The Independent Hungarian Democratic Party, the Civic Democratic Party and the Hungarian Radical Party—the latter two parties as part of the Radical Party Alliance formed the previous year.

The Mindszenty Show Trial

In December 1948, the ÁVH arrested Archbishop of Esztergom József Mindszenty, the charismatic leader of the Roman Catholic Church in Hungary, and several others on charges of espionage, conspiracy to overthrow the republic and foreign-currency racketeering. The ÁVH obtained a confession of guilt from Cardinal Mindszenty after subjecting him to several weeks of interrogation and solitary confinement at the organization’s headquarters at Andrássy Avenue 60 in Budapest.

On February 8, 1949, the Budapest People’s Tribunal sentenced Mindszenty to life in prison and after finding him guilty of treason at the conclusion of a five-day show trial during which the physically and mentally exhausted Archbishop of Esztergom neither explicitly confirmed nor retracted his previous confession (source in Hungarian). In July 1949, the National Council of People’s Tribunals upheld Cardinal Mindszenty’s sentence and commuted those of his three co-defendants to between 4 and 15 years in prison (source in Hungarian).

Dissolution of the Remaining Opposition Parties

In early February 1949, Democratic People’s Party President István Barankovics fled to Austria rather than comply with Hungarian Workers’ Party General Secretary Rákosi’s personal demand that he dissolve the party on the grounds that it had engaged in anti-democratic and anti-people (népellenes) activities and that he publicly denounce the Vatican’s interference in the internal affairs of Hungary in connection with the arrest and prosecution of Archbishop of Esztergom József Mindszenty (source in Hungarian). Eleven other Democratic People’s Party officials soon followed Barankovics into exile, while those who remained in Hungary disbanded the party on February 7, 1949 (source A and B in Hungarian).

Christian Women’s League President Margit Slachta went into hiding at a convent in Hungary in January 1949 to avoid possible arrest, thus putting an effective end to the small National Assembly party (source in Hungarian).

The dissolution of the Democratic People’s Party and the Christian Women’s League signified the end of the National Assembly opposition in Hungary.

The 1949 National Assembly Election

On April 17, 1949, the newly established Hungarian Independent People’s Front (HIPF) issued the alliance’s summons for new National Assembly elections in the Hungarian Workers’ Party daily newspaper Szabad Nép (source in Hungarian):

Workers, peasants, intellectuals and working people are struggling together for a better future: they are going to vote together as well. The agents of the major land-owners, the plutocrats and the foreign imperialists will no longer drive a wedge between us! We have drawn the lesson from four years of unfortunate party-competition, we will not permit the unity of our working people to be broken. There is strength in unity! This is why we are running on a common list.

The Hungarian Workers’ Party leadership determined the distribution of National Assembly mandates among the five constituent parties of the Hungarian Independent People’s Front in the new parliamentary cycle before the election was held. Those participating in the May 15, 1949 election chose between the alternatives of either voting for the Hungarian Independent People’s Front list of candidates, who were not identified according to party, by simply casting their ballots as they received them or voting against the HIPF list by marking a circle at the bottom of the ballot (source in Hungarian).

A total of 97.1 percent of participants voted for the Hungarian Independent People’s Front list in the election, while 2.9 percent of participants voted against the HIPF list. Voter turnout was 94.7 percent (source in Hungarian).

The Hungarian Workers’ Party stipulated the following distribution of the 402 seats in the National Assembly among the five HIPF parties: Hungarian Workers’ Party, 70.9 percent; Independent Smallholders’ Party, 15.4 percent; National Peasant Party, 9.7 percent; Independent Hungarian Democratic Party, 2.5 percent; Hungarian Radical Party, 1 percent; and party-unaffiliated, 0.5 percent, or two representatives intended to embody the ideals of Christian socialism in parliament—the noted historian Gyula Szekfű and the former Democratic People’s Party official Lajos Vörös (source in Hungarian).

Nearly three-quarters of the representatives in the new National Assembly were of working-class or peasant origin, while 71 were women—up from 22 during the previous parliamentary cycle (source A in Hungarian and B in English).

Arrest of Foreign Minister László Rajk

On May 30, 1949, the ÁVH arrested Foreign Minister László Rajk on charges of espionage for foreign powers. Hungarian Workers’ Party General Secretary Mátyás Rákosi and his political allies intended to use Rajk—who had implemented the HWP’s “salami tactics” against rival political parties as interior minister from March 1946 to August 1948—as the main defendant in a show trial exposing agents of Tito and Western imperialism in the party and government (source in Hungarian).

Formation of the Second Dobi Government

Prime Minister István Dobi retained his position as head of government following the May 15, 1949 general election. On June 11, 1949, Dobi formed a new government composed of 18 ministers—13 from the Hungarian Workers’ Party, three, including himself, from the Independent Smallholders’ Party and two from the National Peasant Party (source in Hungarian).

The 13 HWP cabinet ministers included powerful party officials such as Deputy Prime Minister Mátyás Rákosi, State Minister Ernő Gerő, Interior Minister János Kádár, Foreign Minister Gyula Kállai, Defense Minister Mihály Farkas, People’s Education Minister József Révai, People’s Welfare Minister Anna Ratkó and Minister of Light Industry György Marosán.

Adoption of the Constitution of the Hungarian People’s Republic

On August 18, 1949, the National Assembly adopted The Constitution of the Hungarian People’s Republic—the second written constitution in Hungary’s history after that of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. The preamble of the constitution, which was based on the 1936 Soviet Constitution, stated (source in Hungarian):

The armed forces of the great Soviet Union liberated our country from the yoke of the German fascists, crushed the anti-people [népellenes] state power of the major landowners and capitalists and opened the road of democratic progress to our working people. Reaching power through hard struggles against the masters and defenders of the old order, the Hungarian working class, in alliance with the working peasantry and with the generous help of the Soviet Union, rebuilt our country destroyed in the war. . . .

The constitution defined the Hungarian People’s Republic as a “state of the workers and the working peasants” in which “all power belongs to the working people” and “the large majority of the means of production are under the ownership of the state, the public body or cooperatives as social property.”

The Constitution of the Hungarian People’s Republic came into effect on August 20, 1949, thus putting an end to the Second Hungarian Republic.

Conclusion

The Hungarian Communist Party built a single-party dictatorship and planned economy in Hungary within the nominally democratic framework of the Second Hungarian Republic from 1946 to 1949. The proclamation of the Hungarian People’s Republic in the latter year therefore signaled the completion—not the beginning—of communist takeover in the country.

The HCP seized absolute political power in Hungary with heavy external support from the Soviet-dominated Allied Control Commission and the Soviet military via the party’s control of the Interior Ministry, the People’s Tribunals, the National Election Committee and other government and state organizations.

The Mátyás Rákosi–led communists and fellow travelers eliminated both their Christian-nationalist and leftist political rivals through intimidation and spurious charges of electoral fraud, anti-republic conspiracy and espionage for foreign powers, orchestrating show trials that led to the execution of six innocent people and the imprisonment of many others during the three-and-a-half-year existence of the Second Hungarian Republic.

The Hungarian Communist Party was thus able to establish unmitigated political authority in Hungary with the genuine support of only about one-fifth of the country’s electorate, winning only 22.2 percent of the vote in the single multi-party National Assembly election held at the time of the Second Hungarian Republic despite widespread ballot stuffing in its favor.

This transformation from multi-party democracy to one-party dictatorship culminated in the staging of a sham general election shortly before the declaration of the Hungarian People’s Republic in which all participating parties were forced to join a popular front that received over 97 percent of all votes cast.

The HCP oversaw the introduction of a Soviet-type planned economy in Hungary with broad support from both allied left-wing parties and rival Christian-nationalist parties: by the end of 1948, the various coalition governments of the Second Hungarian Republic had nationalized all banks, coal mines and major factories (those with over 100 workers) in the country and laid the legal groundwork for the collectivization of agriculture.

These governments also concluded the agreements that established the conditions necessary for the incorporation of Hungary into the Soviet Bloc: the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty, specifically the stipulation permitting the Soviet Union to keep its military forces in the country; the 1948 Hungarian-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance; and the 1949 treaty establishing the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance.

The history of the Second Hungarian Republic revolves around the subversion rather than the construction of democracy and republican government. However, the Second Hungarian Republic and its ephemeral post-First World War predecessor—both of which succumbed to communist dictatorship—nevertheless laid the political foundations upon which the post-communist Third Hungarian Republic was built.