The Hungarian Soviet Republic

On March 21, 1919, the Party of Communists in Hungary and the radical faction of the Hungarian Socialist Democratic Party came to power in place of the liberal-socialist government of Prime Minister Dénes Berinkey, which had dissolved itself the previous day rather than accede to the demand of the Entente Powers as transmitted via French Lieutenant-Colonel Fernand Vix to further withdraw Hungarian military forces to the western border of a 50-kilometer-wide buffer-zone extending across the Great Hungarian Plain. Party of Communists in Hungary leader Béla Kun and Hungarian Social Democratic Party official Sándor Garbai proclaimed the establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic [Magyar Tanácsköztársaság] in Budapest the same day, thus signifying the end of the short-lived First Hungarian Republic established shortly after the end of the First World War in November 1918.

The Hungarian Soviet Republic itself lasted just three and a half months before the invading army of the Kingdom of Romania overthrew the Béla Kun-led Revolutionary Governing Council, the second communist government in history to exercise sovereign political power after Vladimir Lenin’s Bolsheviks in Russia.

———————————————————————————————————

Coming to Power

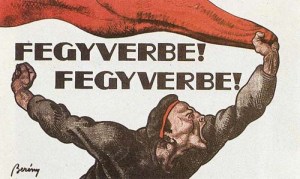

Painting the Hungarian Parliament Building red: Hungarian Social Democratic Party poster from early 1919.

First Hungarian Republic President Mihály Károlyi intended to appoint a new government composed entirely of Hungarian Social Democratic Party ministers following the resignation of the Berinkey government on March 20. However, before President Károlyi could do so, the radical faction of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party under the leadership of trade-union officials Jenő Landler and Sándor Garbai and the Party of Communists in Hungary [Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja] under the leadership Béla Kun merged into the Socialist Party of Hungary [Magyarországi Szocialista Párt] and unilaterally formed a new government on March 21.

On March 22, the newly formed socialist-communist government issued a forged declaration of resignation from President Károlyi, who had intended to remain head of state following the resignation of the Berinkey government, though chose to recognize the quasi coup d’état rather than struggle to preserve his crumbling political power.

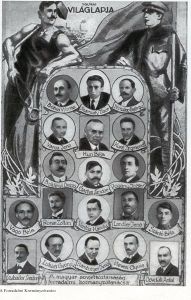

Government

Members of the newly founded Socialist Party of Hungary formed a government called the Revolutionary Governing Council [Forradalmi Kormányzótanács] on March 21. This council served as the executive power in the Hungarian Soviet Republic throughout its 133-day existence. So-called people’s commissars [népbiztos] performed the duties of government ministers in the Revolutionary Governing Council, which rose in number from 15 in its original form to 35 following a reshuffle of the council on April 7.

The Revolutionary Governing Council: Béla Kun (second from top, center); Vilmos Böhm (top, left); Tibor Szamuely (top, center); Sándor Garbai (middle, center); József Pogány (middle, right); and Jenő Landler (second from bottom, second from right), among others.

Sándor Garbai served as the president of the Revolutionary Governing Council in all its configurations, though People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs Béla Kun was the de facto leader of the council. People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs Jenő Landler, People’s Commissar for Military Affairs Vilmos Böhm as well as József Pogány and Tibor Szamuely, both of whom served in various capacities, were the other most powerful figures within the Revolutionary Governing Council. World-famous Marxist philosopher and literary historian György Lukács furthermore served as a mid-level people’s commissar in the Revolutionary Governing Council.

The National Assembly of Councils [Tanácsok Országos Gyűlése] served as the legislative power in the Hungarian Soviet Republic. The National Assembly of Councils formed following indirect national elections held on April 7-8, 1919 in which all Hungarian citizens over the age of 18 were given the right to vote for councils that subsequently delegated representatives from the ruling Socialist Party of Hungary to serve in the legislature. This election represented the first in Hungary in which women were accorded suffrage. However, the council held only a single ten-day session in June 1919 at which it adopted the new constitution of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, the first written constitution in Hungary’s history (text of constitution in Hungarian). In most instances, the Revolutionary Governing Council ruled by decree.

Domestic Policy

Long live the proletarian dictatorship! Temporary communist monument in Budapest at the time of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

The main domestic objective of the Kun-led government was to introduce socialist production in place of capitalist production under the authority of a proletarian dictatorship based on the Marxist model as had taken place in Russia a year and a half previously. The National Assembly of Councils enshrined this objective in the constitution of the Hungarian Soviet Republic adopted in June 1919.

In the name of introducing socialist production, the Kun-led government nationalized factories, shops, schools, residential buildings and land throughout the fluctuating territorial boundaries of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

The Kun-led government’s lack of land redistribution, stated intention to collectivize agricultural production and requisitions of foodstuffs in the countryside to feed the cities greatly antagonized the Hungarian Soviet Republic’s rural population and led to anti-government uprisings in the agrarian region lying between the Danube and Tisza rivers.

The Kun-led government enacted strict separation of church and state in the Hungarian Soviet Republic, nationalizing Church-owned schools, libraries, archives and land through its National Religious Affairs Liquidation Office [Országos Vallásügyi Likvidáló Hivatal]. Although the Revolutionary Governing Council issued a decree guaranteeing the freedom of religious worship, the overwhelming majority of pious citizens of the Hungarian Soviet Republic opposed communism in general and the Kun-led government in specific due to their manifestly anti-Church political ideology (source in Hungarian).

The economic upheaval stemming from the recently concluded war and newly introduced system of state ownership resulted in chronic shortages and high inflation, which served to turn even more of the population of the Hungarian Soviet Republic against the Revolutionary Governing Council. The Kun-led government’s implementation of wage hikes for industrial workers and state employees and reduction of housing rental-costs partially offset the widespread antagonism toward the new communist administration stemming from the shortages and inflation.

Armed Forces and Police

Soon after coming to power, the Kun-led government abolished the Hungarian Royal Army [Magyar Királyi Honvédség], the Hungarian Royal State Police [Magyar Királyi Államrendőrség] and the Hungarian Royal Gendarmerie [Magyar Királyi Csendőrség] and established the Red Army to serve as the military of the Hungarian Soviet Republic and the affiliated Red Guard [Vörös Őrség] to serve as the main law-enforcement organization of the newly founded communist state. The government dismissed much of the commissioned personnel of all three forces and replaced them with politically reliable officers, many of them with little or no experience in positions of command.

The Red Army operated primarily under the command of Commissar for Military Affairs Vilmos Böhm, who had served as defense minister in the Berinkey government before the Kun-led Revolutionary Governing Council came to power. The Red Guard operated under the authority of People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs Jenő Landler. The Red Army raised the number of soldiers serving in the force from 20,000 on April 1 to 54,000 on April 15 and 110,000 on May 14 (source in Hungarian).

Communist-paramilitary commander József Cserny (center) with members of the Lenin Boys (background).

Additionally, People’s Commissar Tibor Szamuely commanded a 200-man paramilitary force known as the Lenin Boys [Lenin Fiúk], which conducted operations aimed at eradicating internal opposition to the Kun-led government and the Hungarian Soviet Republic. The Lenin Boys and another intermittently affiliated paramilitary force under the command of Imperial and Royal Navy veteran József Cserny killed an estimated 590 explicit or presumed adversaries during what came to be known in Hungarian history as the Red Terror [Vörösterror]. The so-called Red Terror claimed a significant proportion of its victims during the suppression of the aforementioned anti-communist rebellion in the region between the Danube and Tisza rivers in May and June. Only 34 of the recorded victims of the Red Terror were from Budapest (source in Hungarian).

External Relations

The Kun-led government did not maintain regular diplomatic relations with the Entente Powers that had defeated Hungary and the other member states of the Central Powers alliance in the First World War concluded in November 1918.

The Entente Powers initiated contact with the Kun-led government shortly after it came to power, sending a delegation under the leadership of British War Cabinet official Lieutenant-General Jan Smuts of South Africa to Budapest on April 4, 1919 with the offer of lifting the alliance’s economic blockade on the Hungarian Soviet Republic if the Kun-led government agreed to withdraw Hungarian Red Army military forces to the border of the military buffer-zone separating Hungarian and Romanian troops stipulated in the Vix Memorandum submitted to the liberal-socialist Berinkey government two weeks previously. However, the Kun-led government rejected this summons, just as the Berinkey government had, insisting that military forces from the Kingdom of Romania withdraw instead to the military demarcation-line designated in the Belgrade Military Convention that the Károlyi government had concluded with the Entente Powers in November 1918 (see The First Hungarian Republic).

The Smuts delegation left Budapest immediately following the failed negotiations with the Kun-led government, the only talks that took place between the Entente Powers preparing the post-First World War treaties at the Paris Peace Conference and the leaders of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic.

The Hungarian Soviet Republic was in a state of undeclared war with both the incipient Czecho-Slovak state and the Kingdom of Romania, which along with the Kingdom of Serbia, were involved in territorial disputes with the communist republic. The Kun-led government did, however, maintain diplomatic relations with the Republic of German-Austria, a short-lived state under the leadership of Austro-Marxist Chancellor Karl Renner composed of the contiguous German-speaking regions of the defunct Dual Monarchy.

The Hungarian Soviet Republic’s only true ally was Soviet Russia. The Kun-led Government attempted to conclude a military alliance with Soviet Russia, sending People’s Commissar Tibor Szamuely to Moscow on May 25 to hold talks with Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin aimed at organizing coordinated military operations against the Kingdom of Romania, which had unilaterally incorporated the Russian-held region of Bessarabia into the Romanian state in April 1918. However, Lenin rejected the proposed military cooperation with the Hungarian Soviet Republic on the grounds that the Soviet Red Army could not spare forces for coordinated military operations against the Kingdom of Romania until it had defeated White Army forces in the Russian Civil War.

Nationalist Opposition

Monarchist and nationalist Hungarian anti-communists who had fled to the Republic of German-Austria after the end of the First World War founded the Antibolsevista Comité [Anti-Bolshevik Committee] in Vienna on April 12, 1919 in order to organize the overthrow of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

The Count István Bethlen-led Antibolsevista Comité orchestrated the theft of a large sum of Austrian currency from the Hungarian Soviet Republic’s embassy in Vienna, some of which local police later recovered, on May 2, 1919 in order to finance the organization’s operations. Four days later, a group of 30-40 military officers under the command of the committee attempted to infiltrate the territory of the Hungarian Soviet Republic just north of Lake Fertő (Neusiedler See) with the objective of fomenting anti-communist revolution in the western part of the country, though withdrew after encountering resistance from Red Army border guards.

The Antibolsevista Comité disbanded shortly after the failed infiltration-attempt due to the establishment of a Hungarian nationalist counter-government under the leadership of Count Gyula Károlyi, a cousin of First Hungarian Republic prime minister and president Mihály Károlyi, in the French-occupied city of Arad on May 5, 1919.

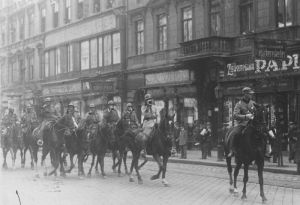

Hungarian Red Army soldiers suppress the Ludovika Military Academy anti-communist revolt in Budapest on June 24, 1919.

This nationalist counter-government, which moved to the similarly French-occupied city of Szeged at the end of May, included Count Gyula Károlyi as prime minister, noted geographer Count Pál Teleki as foreign minister and former Austro-Hungarian Navy Vice-Admiral Miklós Horthy as defense minister. Serving in the latter capacity, Horthy began raising a so-called National Army [Nemzeti Hadsereg] in June 1919 in order to bring a forcible end to the Hungarian Soviet Republic. The size of this anti-communist volunteer force rose to around 30,000 soldiers, many of them veterans of the First World War, by the end of the summer.

On June 24, 1919, cadets and other personnel from the Ludovika Military Academy in Budapest launched a minor armed uprising against the Kun-led Revolutionary Governing Council, bombarding the headquarters of the ruling Socialist Party of Hungary from monitors on the Danube River. However, Red Army, Red Guard and pro-government paramilitary units easily suppressed this rudimentary anti-communist rebellion, which was not connected directly to Horthy’s National Army.

Military Conflict

On April 16, 1919, the Hungarian Red Army launched a preemptive attack on military forces from the Kingdom of Romania deployed along the historical border of the region of Transylvania since the previous January. The objective of the attack was twofold: to prevent the Romanian army from advancing to the military buffer zone stipulated in the Vix Memorandum at the end of March and reconfirmed in the course of direct negotiations between the Kun-led government and the Smuts mission earlier in April; and to drive Romanian military forces from the western border of Transylvania, if possible to the demarcation line specified in the November 1918 Belgrade Military Convention.

However, the Romanian army easily repelled the Hungarian Red Army offensive, launching a counter-attack that passed through the Vix Memorandum-stipulated buffer zone within a week and occupying the Hungarian Great Plain cities of Nagyvárad (Oradea) on April 20 and Debrecen on April 24. Romanian military commanders then decided to unilaterally continue the offensive beyond the designated buffer zone to the Tisza River in order to establish a more defensible front, occupying the city of Nyíregyháza on April 26 and the entire length of the east bank of the Tisza within the Hungarian Soviet Republic by May 1.

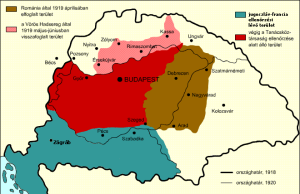

Zones of control within the boundaries of the pre-November 1918 Kingdom of Hungary: red = territory under the control of the Hungarian Soviet Republic throughout its existence; pink = territory the Hungarian Red Army recaptured from the Czecho-Slovak army during the Northern Offensive; brown = territory the Romanian army captured in April 1919; blue = region under control of Serbian army. Note that the uncolored areas represent territory under the control of the Czecho-Slovak army (north) and Romanian army (east) at the time of the proclamation of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

On April 27, Czecho-Slovak military forces under the command of Italian General Luigi Piccione and French General Edmond Hennocque took advantage of Hungarian Red Army troop movement along the upper Tisza at the time of the Romanian offensive to advance beyond the military demarcation line that Lieutenant-Colonel Vix had dictated to the Károlyi government on December 23, 1918 (see The First Hungarian Republic), occupying the cities of Sátoraljaújhely and Munkács on April 30 and Miskolc on May 2.

On May 20, the Hungarian Red Army launched an attack known as the Northern Offensive [Északi Hadjárat] aimed at the driving Czecho-Slovak army back to the Hungarian-Slovak linguistic border as stipulated in the December 1919 Bartha-Hodža agreement and establishing direct contact with Soviet Russia via the portion of Galicia under the control of pro-Bolshevik forces.

This offensive, conducted under the command of Revolutionary Governing Council People’s Commissar for Military Affairs Vilmos Böhm and Hungarian Red Army Chief of Staff Aurél Stromfeld, achieved the first objective of driving Czecho-Slovak military forces back to the Hungarian-Slovak linguistic border early in the second week of June and the second objective of establishing a corridor linking the Hungarian Soviet Republic to Soviet Russia via pro-Bolshevik forces in Galicia on June 16.

The Hungarian Red Army established a puppet government in the city of Eperjes (Prešov) on June 16 under the leadership of Czech communist Antonín Janoušek and including future high-ranking Hungarian communist official Ferenc Münnich, among others. This puppet government composed of communists and those who otherwise opposed Czecho-Slovak unification declared the foundation of the Slovak Soviet Republic in the predominantly Slovak-inhabited corridor between the Hungarian Soviet Republic and pro-Bolshevik Galicia under the occupation of the Hungarian Red Army.

On June 7 and 13, 1919, Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau of France sent memoranda to the Kun-led government in the name of the Paris Peace Conference offering to secure the withdrawal of troops from the Kingdom of Romania from the Tisza River back toward the historical border of Transylvania and to invite representatives from the Hungarian Soviet Republic to participate in the peace conference if the government ordered the withdrawal of Hungarian Red Army troops from areas retaken from the Czecho-Slovak military forces in the course of the Northern Offensive. The Kun-led government agreed to this proposal over the vigorous objections of Hungarian Red Army Chief of Staff Aurél Stromfeld, who resigned from his post in protest, signing an armistice with the Czecho-Slovaks on June 23 and beginning the withdrawal stipulated in the Clemenceau memoranda on June 30. The Slovak Soviet Republic collapsed following the Hungarian Red Army’s withdrawal from the region on July 7.

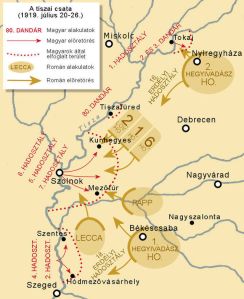

The Romanian army did not, however, withdraw from the Tisza River pursuant to the conditions specified in the Clemenceau memoranda to the Revolutionary Governing Council. The Kun-led government therefore decided to launch an attack on the Romanian military forces deployed along the Tisza in order to enforce the stipulations of the memoranda. The Hungarian Red Army began bombarding Romanian positions along the Tisza on July 17, crossing the river in direct attack from three locations on July 20: the town Tokaj in the north; Szolnok in the center; and opposite Mindszent in the south.

Hungarian-Romanian fighting along the Tisza River in July 1919: red arrowed lines = Hungarian Red Army attacks; red dotted lines = extent of territory occupied in attacks; brown arrowed lines = Romanian army counterattacks.

The Hungarian Red Army drove the Romanian army back about 15 kilometers in the north and the south and about 35 kilometers in the center until the offensive stalled on July 23. Romanian military forces then launched a counter-attack on July 24, gradually forcing the Hungarian Red Army to surrender the territory it had recaptured east of the Tisza. The Romanian army crossed the Tisza River just north of Szolnok on July 29, forcing the Kun-led government’s military forces into full retreat the next day.

After crossing the Tisza, the Romanian army advanced toward Budapest without encountering significant resistance from the crumbling Hungarian Red Army, reaching the capital city on August 3.

An estimated 11,000 soldiers died in battle during the Hungarian Soviet Republic’s armed conflicts with the Kingdom of Romania and the incipient state of Czechoslovakia—6,000 from the Hungarian Red Army, 3,000 from the Romanian army and 2,000 from the Czecho-Slovak army (source in English).

Downfall

Béla Kun and other members of the Revolutionary Governing Council fled to the Republic of German-Austria in order to avoid capture on the part of the approaching Romanian army on August 1, the recognized date of the collapse of the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Berinkey-cabinet Labor Affairs and Public Welfare Minister Gyula Peidl formed a transitional government on August 1 composed solely of members of the pre-merger Hungarian Social Democratic Party, including Revolutionary Governing Council President Sándor Garbai.

Meanwhile, the main body of the Romanian army under the command of General Traian Moşoiu occupied the city of Budapest on August 4 and 5. With the help of Romanian military forces, the leader of the anti-communist organization the White House Fraternal Association [Fehérház Bajtársi Egyesület], Friedrich István, and his associates seized power from the Peidl government, signaling the end of three and a half months of Marxist political administration in Hungary.

Fate of the People’s Commissars

All of the most powerful people’s commissars within the Revolutionary Governing Council fled to the Republic of German-Austria in early August 1919, either before the arrival of Romanian troops to Budapest or following after the collapse of the short-lived Peidl government.

Lenin Boys commander Tibor Szamuely died of a gun-shot wound to the head, perhaps self-inflicted, after encountering an Austrian police officer shortly after fleeing across the border into the Republic of German-Austria on August 2, 1919.

Revolutionary Governing Council leader Béla Kun and member József Pogány both went into permanent exile in Soviet Russia, where they became officials in the Communist International before being executed on charges of Trotskyism during the Stalinist purges in the late 1930s.

Revolutionary Governing Council President Sándor Garbai, People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs Jenő Landler and People’s Commissar for Military Affairs Vilmos Böhm all eventually left the increasingly right-wing Republic of Austria and died in exile of natural causes, Garbai and Landler in France and Böhm in Sweden.

Communist paramilitary leader József Cserny and 13 of those who had acted under his command were executed, along with seven members of the Lenin Boys, in December 1919 after a court condemned them to death for murders committed at the time of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Jewish Aspect

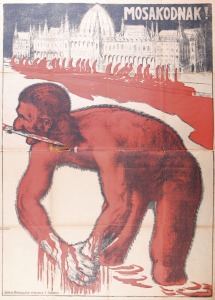

Red flows from the Hungarian Parliament Building: Anti-Semitic poster associating Jews with the fallen Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Many of the high-ranking leaders of the Hungarian Soviet Republic were Jews, including Kun, Pogány, Landler, Böhm and Szamuely. The websites Holokauszt Magyarországon [Holocaust in Hungary] and Szombat [Saturday] estimate that between 45 percent and 75 percent of the leaders of the Hungarian Soviet Republic were Jews.

The above circumstance served as the foundation, subsequently reinforced during the period of largely Jewish Stalinist rule in the late 1940s and early 1950s, for the widespread cognitive association in Hungary between communism and Jews and, consequently, of the close relationship in the country between anti-communism and anti-Semitism.